Whereas most websites are created to generate business, this website is a review of images and projects in my fifty-year career as an ethnographic photographer. The phrase that describes it is… ‘Photography of the indigenous peoples of the Americas’ (and the rest of the world).

I consider myself lucky to have had the trust of clients (educational publishers and international development organizations) to also do exotic travel. Before photography became digital, the film stock and travel expenses would be spent before seeing one picture. I’d shoot for a month…or two. Things like dust, heat, X-rays, and theft were hazards. The digital age started right in the middle of my career. The changes were tremendous; mostly for the better.

My work with the Maya produced the biggest thrills.

To do this work I had to exploit the personal qualities of my essential being that allowed me to approach strangers (often with no shared language ) and to make them feel comfortable being photographed. I was good at getting people to give it a try… and that we’d stop if it didn’t go well. In some Maya towns, the rules said ‘no photography’ but as a professional, I was willing to push it. The story of getting arrested is a good one.**

The Maya world I stepped into was traditional; mud brick homes with grass roofs. In the cocina there were no manufactured goods; the most modern thing was one 60-watt lightbulb. Imagine trying to make pictures with the slow films of the late ‘70s, with dark adobe walls, and a ceiling that was black from fires with no chimney gobbling up the light. (Solution: push processing, and clip tests.)

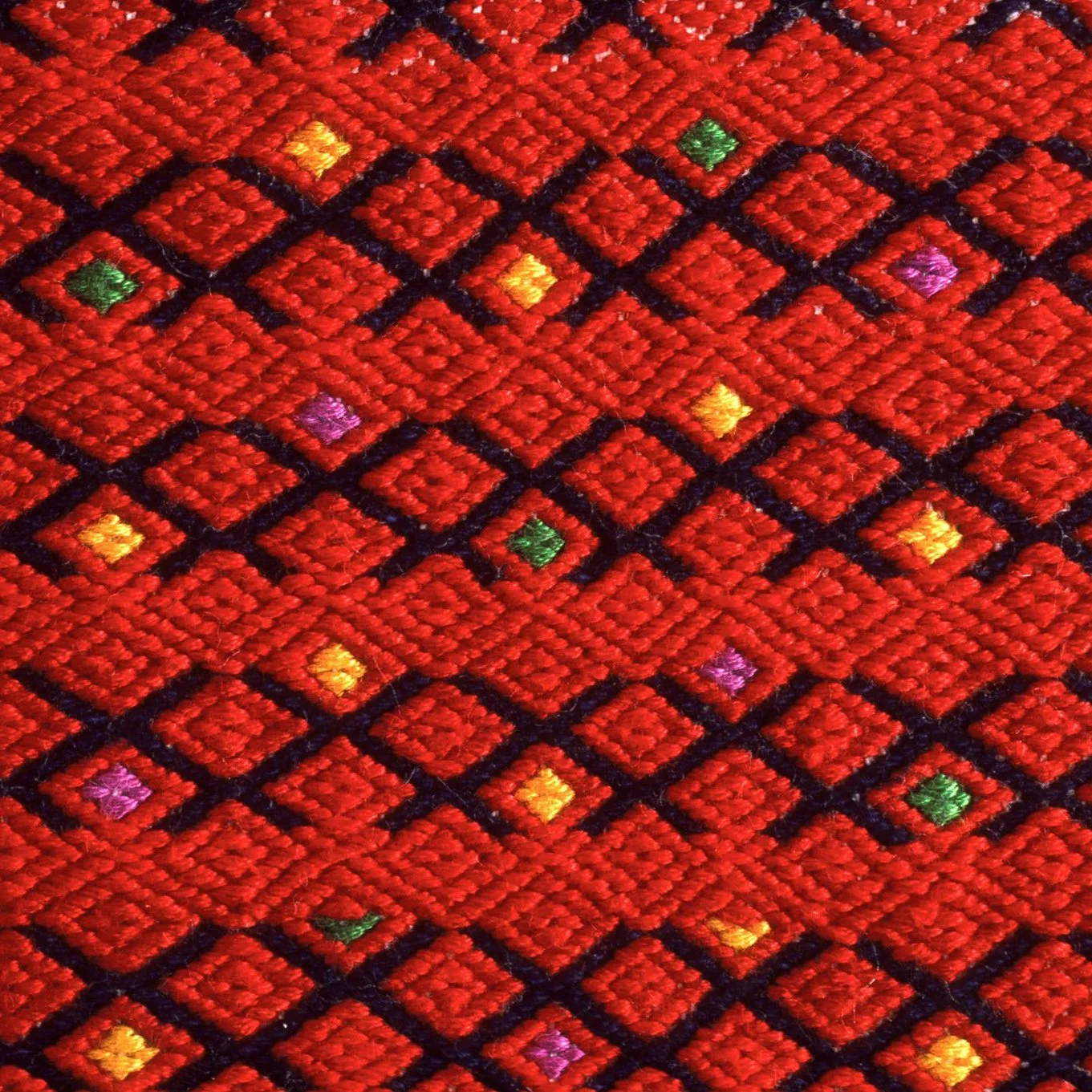

I knew the pictures were special. At a museum Christmas party in NYC in ’85, I chanced to meet an editor from the Abrams Publisher and got the opportunity to show her the work. Also, very important, is that the writer of the book would be one of the first McArthur Fellows…Walter F. Morris, Jr., (Chip) a central figure in interpreting the iconography in Maya textiles, and a prime organizer of the weavers into a cooperative called Sna Jolobil. The book Living Maya (1987) won the Anisfield-Wolf Award—also won by Martin L. King, Jr. and Langston Hughes—for promoting inter-racial understanding.

My good fortune continues. As I saché to my dead end I take pleasure looking back at a satisfying career. In ’78 I photographed for the Science Museum of MN when they were making their Maya textile collection. Chip Morris was the expert guiding Louis Casagrande, PhD., Curator of Anthropology. Recently they got a grant to put the collection online. The pictures I was making back then document what they were collecting. The Foxx Maya Archive images will reside in the Science Museum of Minnesota for posterity… securing my legacy, and giving to the Maya in Chiapas digital access to the images of their ancestors on their cell phones.

I realized that I wouldn’t be satisfied as a ‘one-book photographer’. The next project that interested me was the Native American turquoise jewelers in the Southwest. Entering pueblos I soon realized that the New York State license plates on my VW van were causing people to back off; I changed to New Mexican plates and the problem vanished. The photography got good reviews in The Torquise Trail: Native American Jewelry of the Southwest (1993). Spending two years in the Southwest was refreshing. And, I published a third Abrams book shot in Guatemala: The Maya Textile Tradition (1997).

I want you to know that none of these projects happen without help. The rule of thumb in photography is: “don’t hire anybody who isn’t better than you.” Christiana Dittmann has been in my photographic life 50 years. We photographed the universality of childhood in eleven countries; we entered Maya together. Cristina Taccone, a fine photographer, worked with me in Chiapas in ’86.

1986 is a year when things were going well. I felt certain that the Maya images were special. It’s probably because I’m a New Yorker and felt I had to go to ‘the mountain top’ to show the work… the publishers up there were LIFE Magazine, and the Abrams Publisher. National Geographic was obvious.

In Chiapas I befriended George Stuart, a National Geographic Society staff archaeologist. George was a true Mayanist. In D.C. he introduced me to the important NGS executives and got me a nice check and a hundred rolls of Kodachrome. It was a dream come true. It didn’t make the photography go more smoothly; it was still challenging if not more so. I cherish this quote from George:

“… your collection is one of almost supernatural merit, based not only upon what I have seen in the distant past, but upon the reaction that Melinda and I had to the images you appended to your email. I have seen thousands of Maya photographs, but hardly any like those!”

One quote comes from the Director of Photography at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. I met Jeff Rosenheim at the opening of an exhibit; the first pictures of Yosemite. He was describing the challenges to the photographer, Carleton Watkins, dealing with threatening Indians and hazards to his equipment and horse-drawn wagon. I interrupted to say that it was similar to the hazards I encountered driving my VW Camper (100 hours) down to Chiapas. Rosenheim gave me his business card… which could only be interpreted as ‘show me your pictures’… and I did… by email. His response changed my perception of my photography career: though he had no need for my images, he wrote: “Know that I appreciate your work and I like the way you present yourself.” My approach was informal. Rosenheim represents the critical eye of the premiere art museum on the planet… and he liked my pictures!

At 82 I’m continually surprised at the creeping finality of so many aspects of this accomplished successful life. It was a great trip. I hope you enjoy the images.

Thanks,

Jeff.

**Arrest story:

Chip and I went to Chamula to partake in the Carnival fiesta. It’s a big one over a large area. Everyone was having a good time. Some people were in costume…as was Chip. He was wearing a Bullwinkle Moose hat. My usual outfit with long-lens camera in that setting fit in.

In a flash I came up with the solution! “Let me give each of you a Polaroid picture.” They liked that…but that camera was in my van. At that moment we were all of one mind. The offense became theater; they let me get the camera and I returned.

A technical moment arrived that could have turned it into a mess. In order to get the right exposure I had no choice but to point the film camera at them. So there I was, arrested for taking pictures, with my Nikon pointed at them… and I decided to shoot the pictures on film… then shoot the Polaroids. It worked out well. This image shows the officials with Polaroids in their hands. All ended well.

All of a sudden a small man with a big stick grabs my arm… like a vice grip. He was too strong to simply push him away; he was a cop. I was arrested for taking pictures. Nothing Chip said made it go away…and the cop led me to the bench where all the political and religious leaders were sitting. Rather than stand looking down at them I sat on the ground; Chip stood near to translate. (In a sense, the arrested gringo was entertainment.)